October 29, 2022

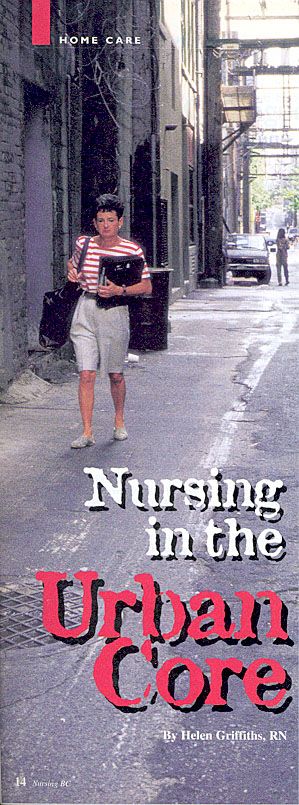

Nursing in the Urban Core

by Helen Griffiths, RN

Vancouver's Urban Core

8,000 plus people74% malepoorest area of the citydouble the mortality compared to the rest of BC5,000 registered with the needle exchange programmore than 600 known people who are HIV positiveaverage of one new sero-conversion a day (50% of all B.C. sero-conversions

8,000 plus people74% malepoorest area of the citydouble the mortality compared to the rest of BC5,000 registered with the needle exchange programmore than 600 known people who are HIV positiveaverage of one new sero-conversion a day (50% of all B.C. sero-conversions

Just off the street past a needle exchange bucket, through a wire cage door and to the left lies the office of the Portland Hotel. This morning it is also a make-shift nursing treatment room. Home care nurses Evanna Brennan and Susan Giles are gently buzzing around their first client of the day. He sits upright in a chair wearing little more than an incontinence garment, revealing emaciated and deeply scarred limbs, punctuated by several crater-like lesions.

"Pyribenzamine is his drug of choice," Brennan explains as she and Giles work together with ointment and dressings in smooth efficient movements that seem almost choreographed.

"Is this a new shoot right here Peter?" Brennan asks as she closely examines a problem area near Peter's thigh. "You've got to shoot away from the top of your leg, okay?"

"Pyribenzamine is his drug of choice," Brennan explains as she and Giles work together with ointment and dressings in smooth efficient movements that seem almost choreographed.

"Is this a new shoot right here Peter?" Brennan asks as she closely examines a problem area near Peter's thigh. "You've got to shoot away from the top of your leg, okay?"

Pyribenzamine, I learn later, is an inexpensive, easily obtained antihistamine. When injected regularly it causes deep wounds that often undermine to form craters and eventually keloid scarring, which limits mobility. It's just one of the many challenges Brennan and Giles face daily on their rounds in the urban core of Vancouver where drugs are a way of life, HIV sero-conversions account for half of those in B.C., and the mortality rate is twice that of other areas in the province.

A few years ago, after returning to work in the downtown eastside, Brennan and Giles noticed a big change in the population. Compared with five years earlier, there were "more drugs, more AIDS and generally more sickness," says Giles. "And there were more young people involved too."

"We asked ourselves, 'What are we going to do when these people reach end-stage in their illness?'" Brennan continues. "Then, within three months we could see it starting to happen."

One of the biggest problems they had as nurses was connecting with the people who needed their care. More often than not, clients just weren't around when they came by. "Traditionally in the home care system," says Giles, "a client is discharged after missing three visits. That doesn't work with people who are transient, possibly confused, and often mistrusting of authority. And with end-stage complications, regular treatment is critical. We realized we had to develop a relationship with these people by any means possible."

This realization led to a period of research by Brennan and Giles to see how other health care workers were managing in similar situations. Locally, they compared notes with the Ministry of Health street nurses, prison nurses and staff at St. Paul's Hospital. They also attended a workshop called "Sex and Drugs 101" put on by the B.C. Centre for Disease Control. Careful timing with conferences and holidays allowed them to also check out programs in Montreal, Seattle and San Francisco.

The upshot of all of this was development of a new program at the Portland Hotel offering a vastly different approach to home nursing care. It centres around creating a trusting relationship with clients that will allow the nurses to minimize the potential hazards of drug abuse, improve the client's general health status, and eventually empower the client in a way that may be the starting point for drug treatment. The focus, however, is on reducing harm rather than on the sometimes unrealistic goal of reducing drug abuse.

This means that now when Brennan, Giles and an accompanying physician attend the Portland on their regular twice weekly visits, they offer teaching about vein maintenance. Along with non-judgmental advice about hygiene and the use of new or bleach-cleaned equipment, comes information about good tying-off technique, knowing where to shoot, and the importance of "saving" one vein. Teaching about community health resources such as the needle exchange, the street nurse program, drug treatment options, and AIDS service groups is also offered.

The nurses' approach to wound care has changed significantly as well. It's guided primarily by the client's pain tolerance, attention span and general preference. While a few clients prefer standard gauze dressings, Brennan and Giles have found that silver sulfadiazine cream (antifungal, antibiotic and possibly antiviral) covered with a hydrocolloid dressing offers some distinct advantages. It occludes the wound leaving access to other potential injection sites, and is less likely to be removed by the client minutes later. The main thing is to cover the wound in a way that is clean, quick and acceptable to the client.

To further encourage client participation, a reward system has been developed. Daily cigarettes and pocket money are distributed by the hotel coordinator after clients have seen the nurses. Brennan and Giles also hand out popular nutritional supplements following care (even if "care" is only a short chat).

Eighteen months later, long-term clients are lining up to see the nurses, new ones are dropping by based on word-of-mouth, and there's generally increased client involvement in care. The end result seems to be better outcomes in the area of wound healing and infection resolution, along with reduced emergency department admissions for cellulitis and abscesses.

Now Brennan and Giles are applying the same approach to building trust with clients at a drop-in centre for street-involved women. "They tend to work all night and sleep all day so they have less access to resources," says Brennan. "And trust is a big issue."

So far, their efforts seem to be paying off. "They vote with their feet," says Giles. "And we're getting more feet all the time."

With such positive outcomes, Brennan and Giles have been keen to share their findings. Informally, they do that on a regular basis when they exchange information with the street nurses, the native health nurse, neighborhood physicians, and a local housing advocacy group. They also sense greater interest in their contributions at St. Paul's AIDS rounds. More formal presentations, sometimes complete with slides, have been well received by nurses at Vancouver Hospital and Health Sciences Centre, and by mental health nurses in the area.

Perhaps the most exciting way they have been able to share their work, however, was with a poster display at an international conference on AIDS in Vancouver this past summer. Accepted as one of 1,000 daily presentations from health professionals across the world, theirs was a "traffic stopper" says Brennan.

This really came as no surprise, however. Poignant images of life on the streets, close-ups of sad, hollow faces and strange, disfiguring wounds, along with a few carefully chosen words about the need to empower clients by returning their sense of control says far more than a lecture ever could. A professor from Harvard University was eager to talk further with the nurses, a local prison nurse invited them to speak in the jail, and even their own colleagues were struck by the presentation.

Brennan and Giles say they would like to see their work expand to other facilities such as food shelters. Another major step would be to find a way to do IV antibiotic therapy in clients' rooms. It would be less expensive, better accepted and more effective than a one week hospital admission, which is usually sabotaged after four days by a client anxious to get back to the streets.

In the meantime though, Brennan and Giles take their satisfaction from more modest achievements. Like the fact that as we leave the Portland Hotel, one of the clients says, "See you next Tuesday." Here, that is progress.

For nurses online, more information on Brennan and Giles' work can be found on their Web Site at www.multidx.com. Their E-mail address is multidx@multidx.com.

(Reprinted from Nursing BC, November-December 1996, pp. 14-16)

A few years ago, after returning to work in the downtown eastside, Brennan and Giles noticed a big change in the population. Compared with five years earlier, there were "more drugs, more AIDS and generally more sickness," says Giles. "And there were more young people involved too."

"We asked ourselves, 'What are we going to do when these people reach end-stage in their illness?'" Brennan continues. "Then, within three months we could see it starting to happen."

One of the biggest problems they had as nurses was connecting with the people who needed their care. More often than not, clients just weren't around when they came by. "Traditionally in the home care system," says Giles, "a client is discharged after missing three visits. That doesn't work with people who are transient, possibly confused, and often mistrusting of authority. And with end-stage complications, regular treatment is critical. We realized we had to develop a relationship with these people by any means possible."

This realization led to a period of research by Brennan and Giles to see how other health care workers were managing in similar situations. Locally, they compared notes with the Ministry of Health street nurses, prison nurses and staff at St. Paul's Hospital. They also attended a workshop called "Sex and Drugs 101" put on by the B.C. Centre for Disease Control. Careful timing with conferences and holidays allowed them to also check out programs in Montreal, Seattle and San Francisco.

The upshot of all of this was development of a new program at the Portland Hotel offering a vastly different approach to home nursing care. It centres around creating a trusting relationship with clients that will allow the nurses to minimize the potential hazards of drug abuse, improve the client's general health status, and eventually empower the client in a way that may be the starting point for drug treatment. The focus, however, is on reducing harm rather than on the sometimes unrealistic goal of reducing drug abuse.

This means that now when Brennan, Giles and an accompanying physician attend the Portland on their regular twice weekly visits, they offer teaching about vein maintenance. Along with non-judgmental advice about hygiene and the use of new or bleach-cleaned equipment, comes information about good tying-off technique, knowing where to shoot, and the importance of "saving" one vein. Teaching about community health resources such as the needle exchange, the street nurse program, drug treatment options, and AIDS service groups is also offered.

The nurses' approach to wound care has changed significantly as well. It's guided primarily by the client's pain tolerance, attention span and general preference. While a few clients prefer standard gauze dressings, Brennan and Giles have found that silver sulfadiazine cream (antifungal, antibiotic and possibly antiviral) covered with a hydrocolloid dressing offers some distinct advantages. It occludes the wound leaving access to other potential injection sites, and is less likely to be removed by the client minutes later. The main thing is to cover the wound in a way that is clean, quick and acceptable to the client.

To further encourage client participation, a reward system has been developed. Daily cigarettes and pocket money are distributed by the hotel coordinator after clients have seen the nurses. Brennan and Giles also hand out popular nutritional supplements following care (even if "care" is only a short chat).

Eighteen months later, long-term clients are lining up to see the nurses, new ones are dropping by based on word-of-mouth, and there's generally increased client involvement in care. The end result seems to be better outcomes in the area of wound healing and infection resolution, along with reduced emergency department admissions for cellulitis and abscesses.

Now Brennan and Giles are applying the same approach to building trust with clients at a drop-in centre for street-involved women. "They tend to work all night and sleep all day so they have less access to resources," says Brennan. "And trust is a big issue."

So far, their efforts seem to be paying off. "They vote with their feet," says Giles. "And we're getting more feet all the time."

With such positive outcomes, Brennan and Giles have been keen to share their findings. Informally, they do that on a regular basis when they exchange information with the street nurses, the native health nurse, neighborhood physicians, and a local housing advocacy group. They also sense greater interest in their contributions at St. Paul's AIDS rounds. More formal presentations, sometimes complete with slides, have been well received by nurses at Vancouver Hospital and Health Sciences Centre, and by mental health nurses in the area.

Perhaps the most exciting way they have been able to share their work, however, was with a poster display at an international conference on AIDS in Vancouver this past summer. Accepted as one of 1,000 daily presentations from health professionals across the world, theirs was a "traffic stopper" says Brennan.

This really came as no surprise, however. Poignant images of life on the streets, close-ups of sad, hollow faces and strange, disfiguring wounds, along with a few carefully chosen words about the need to empower clients by returning their sense of control says far more than a lecture ever could. A professor from Harvard University was eager to talk further with the nurses, a local prison nurse invited them to speak in the jail, and even their own colleagues were struck by the presentation.

Brennan and Giles say they would like to see their work expand to other facilities such as food shelters. Another major step would be to find a way to do IV antibiotic therapy in clients' rooms. It would be less expensive, better accepted and more effective than a one week hospital admission, which is usually sabotaged after four days by a client anxious to get back to the streets.

In the meantime though, Brennan and Giles take their satisfaction from more modest achievements. Like the fact that as we leave the Portland Hotel, one of the clients says, "See you next Tuesday." Here, that is progress.

For nurses online, more information on Brennan and Giles' work can be found on their Web Site at www.multidx.com. Their E-mail address is multidx@multidx.com.

(Reprinted from Nursing BC, November-December 1996, pp. 14-16)